Downwinders: That's you and me.

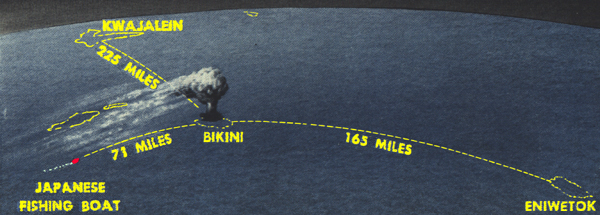

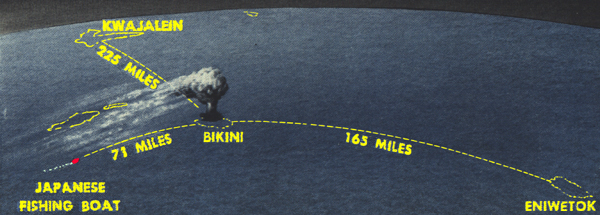

In 1954 a Japanese fishing trawler, the Fortunate Dragon, just happened to be downwind from an atomic test blast in Bikini Atoll. They were 14 miles outside the exclusion zone when the blast occurred. Some of them watched the explosion 71 miles away. It could also be seen from Eniwetok, 165 miles from the blast.

-- The above image is from: Life Magazine, page 19, March 29th, 1954 (color highlights added, text size adjusted, etc., for Internet viewing, by this author).

A few hours after the explosion, deckhands noticed a dusting of white ash, like fine talc. Their eyes and exposed skin became itchy, and they felt a burning sensation, similar to a sunburn or windburn, which they were familiar with, and so they didn't worry too much at first.

They tried to wash all the dust off, but then afterwards, they used the same ropes and tackle which had been left out the whole time, and their hands became painfully sore, swollen, and blistered. Their faces began to turn a "pencil-lead color". They turned for home, some 2,000 miles away, but this was just the beginning of a tragic story, which would eventually lead to death for many of the crewmembers on board the unfortunate ship.

The exclusion zone for atomic tests was widened somewhat, following this international scandal.

But the testing continued.

Below are two data sheets containing wind roses, followed by four drawings of wind patterns for nuclear weapons releases. These are followed by a comparison of the fallout pattern for a nuclear weapon versus for a nuclear weapon used to attack a nuclear power plant. Finally, a fallout map for all-out war against the United States is shown.

Wind roses show the direction of winds over a spot on the Earth during a period of time, for example, three months or one year.

-- The above image is from: Draft Environmental Impact Statement for a Geologic Repository for the Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel and High-Level Radioactive Waste at Yucca Mountain, Nye County, Nevada, Volume 1 -- Impact Analyses, Chapter 3, page 13, U.S. Department of Energy, DOE/EIS-0250D, July, 1999 (colorized and adjusted for Internet viewing by this author).

Developing accurate wind roses is just the first step in trying to determine who might have been been harmed by a radiation release. For a smoldering nuclear reactor, it can be assumed that at some point in the future of that reactor, the winds will go in all possible directions. How far radionuclides will carry depends on many additional factors. What temperature is the air that they are released into -- how high up does it carry the particles? What kinds of particles are being released?

The wind roses shown below were prepared by NASA for the Cape Canaveral / Merritt Island Land Mass, in 1986. Ten years later NASA was still using them, for example, in the Environmental Impact Statement for their Cassini space probe, which carried 405,000 Curies of plutonium (mostly Pu 238). NASA has launched millions of Curies of Plutonium from Florida and California, despite worldwide protest.

-- The above image is from: Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Cassini Mission, page 3-12, June, 1995 (adapted for the Internet (including colorization) by this author).

Below is the fallout pattern for an actual nuclear blast of 11.5 Kilotons ("Shot No. 1", code name "Boltzman") in Nevada in May, 1957, from a 500-foot tower:

-- The above image is from: Health Effect of Low-Level Radiation, Volume 1, page 310, Joint hearing before the 96th Congress, First Session, April, 1979 (scanned and clarified by this author).

Below is the fallout pattern for another Nevada blast, one of 44-Kilotons ("Shot No. 16", code name "Smoky"), on August 31st, 1957, from a 700 foot tower. Note the fallout patterns go in approximately 90 degree different directions from the image above.

-- The above image is from: Health Effect of Low-Level Radiation, Volume 1, page 311, Joint hearing before the 96th Congress, First Session, April, 1979 (scanned and clarified by this author).

Below are more generalized dispersal patterns for nuclear blasts, for a 15 mph "effective wind". (Actual values would probably be less than half those given because the calculations assumed measurements on a flat plane, three feet above the ground, while real measurements would have to account for the increased surface area of the ground over a mathematically perfect, flat plane. As noted in the drawings' original caption, the 30 mile mark is always in the heaviest fallout area.)

-- The above image is from Radiation Protection: A Guide for Scientists and Physicians, Third Edition, by Jacob Shapiro, page 418, Harvard University Press, MA, 1972, 1981, 1990 (colorized and relative text size adjusted for clarity by this author). (According to the caption, the original source was DCPA, 1973.)

In the drawing below, a one-megaton blast at the Detroit Civic Center is assumed. The pattern shown is the main fallout pattern, assuming a 15-mph northwest wind. Contours are for one-week accumulated dose, assuming no shielding, of 3000, 900, 300, and 90 rem.

-- The above image is from Radiation Protection: A Guide for Scientists and Physicians, Third Edition, by Jacob Shapiro, page 419, Harvard University Press, MA, 1972, 1981, 1990 (colorized by this author). (According to the caption, the original source was OTA, 1979.)

Although the heaviest contamination is usually to the local landscape, radioactive fallout travels all around the world. And kills all around the world.

Below is a graphic showing the worldwide distribution for radionuclides, with both "smoke" and "no smoke" assumptions about the global atmospheric climate at the time of the nuclear blasts.

-- The above image is from, Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War, SCOPE 28, Volume 1: Physical and Atmospheric Effects, Second Edition, page 261, Scientific Committee for Problems in the Environment, John Wiley & Sons, 1985, 1989.

In an all-out nuclear war, large portions of the country would be blanked with fallout. The graphic below shows the "500-rad, 1 week minimum isodose contours". To create this graphic it was assumed that 1,000 U.S. cities would be targeted with 1 Megaton, 50% Fission weapons. Nearly constant westerly winds were assumed.

-- The above image is from, Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War, SCOPE 28, Volume 1 Physical and Atmospheric Effects, Second Edition, page 247, Scientific Committee for Problems in the Environment, John Wiley & Sons, 1985, 1989 (colorized by this author). (Original caption notes that the graphic was "taken from Harvey, 1982".)

Nuclear war is bad. We all know that (or read this author's EFFECTS OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS essay, if you're unsure). But how does it compare to a catastrophe at a nuclear power plant?

It's small potatoes, that's how!

Below is a stark, stunning portrayal of this comparison.

Area "A" in the image below is the heavy fallout area for a nuclear weapon -- like the graphics seen in the above illustrations. Area "B" in the image below is the heavy fallout area for a nuclear attack on a nuclear power plant! Which would YOU rather have ruin your day? (NEITHER, THANK YOU VERY MUCH!)

-- The above image is from, Environmental Consequences of Nuclear War, SCOPE 28, Volume 1 Physical and Atmospheric Effects, Second Edition, page 271, Scientific Committee for Problems in the Environment, John Wiley & Sons, 1985, 1989 (colorized by this author).

Combining these scenarios, we get the following graphic:

-- Above image is from: Nuclear Power Plants as Weapons of the Enemy: An Unrecognized Military Peril, by Bennett Ramberg, page 108, Univ. of Calif. Press, California, 1984. (The original caption states that the source was "Chester and Chester, "Civil Defense Implications for the U.S. Nuclear Power Industry", p. 334" and suggests going there, for more information.)

The above drawing was labeled "Year 2000 Nuclear Weapons Attack on Dispersed U.S. Reactors and Reprocessing Plants -- Ten-Year Waste Storage". Below is a close-up of the index from the above image:

-- Above image is from: Nuclear Power Plants as Weapons of the Enemy: An Unrecognized Military Peril, by Bennett Ramberg, page 108, Univ. of Calif. Press, California, 1984.

The amount of waste now in storage at each nuclear power plant is more like 25 years, on average, not 10.

Copyright (c) 2002 by Russell D. Hoffman. All Rights Reserved